At the beginning of the month (August 2025), the Security Cabinet approved Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s proposal to conquer the Gaza Strip. Based on reports published in the media, most cabinet members supported the plan. The vote was held on each clause separately. In practice, the cabinet approved five principles that, from Israel’s perspective, constitute the conditions for ending the war: dismantling Hamas’s military capabilities, returning all hostages—both living and dead—demilitarizing the Gaza Strip, maintaining Israeli security control in the Strip, and establishing a civilian administration that is neither Hamas nor the Palestinian Authority.

Shortly before the cabinet convened, the prime minister gave an interview to the American network Fox News and confirmed Israel’s intention to conquer the Strip. He emphasized: “The goal is to ensure our security, remove Hamas, and enable the Gazan population to be freed from it. I intend to transfer control of the Strip to a civilian administration that is not made up of Hamas nor of any entity that promotes the destruction of Israel. That is what we want to do—to free ourselves and the residents of Gaza from Hamas.” Netanyahu added: “We want a buffer zone (a security perimeter) between Israel and the Strip,” stressing that this will not be possible as long as Hamas remains there.

Before the cabinet meeting, the prime minister also held a press conference with India’s ambassador to Israel, J.P. Singh, followed by a meeting with Indian journalists. In response to a question from a journalist with the Indian channel CNN-News18, Netanyahu presented his strategic vision regarding the continuation of the campaign in Gaza the day after Hamas, saying: “Israel will not annex the Gaza Strip… The goal is to transfer control of the territory for a transitional period to a governing body that will administer the Strip after the end of Hamas’s rule.” He further stressed that the war aims remain as initially defined: “The destruction of Hamas and the return of all Israeli hostages. The war could end tomorrow morning if Hamas lays down its weapons and releases the hostages unconditionally.” Israel, he added, also plans to establish a “security belt” to ensure that Hamas or other terrorist elements will no longer pose a threat to it in the future.

According to media reports, Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Eyal Zamir expressed opposition to the conquest of the Strip during the cabinet session, warning of the problematic implications involved—chief among them, harm to the hostages and further attrition of IDF forces. Nevertheless, he emphasized that under his command, the IDF would carry out any mission assigned by the political echelon. He presented an alternative course of action to conquering Gaza—through a maneuver of encirclement—and noted that, from his perspective, this was the preferred option.

Israeli Investment in Local Infrastructure

The government’s decision to take control of the Gaza Strip, although not explicitly and directly addressing the possibility of imposing a military government there, nevertheless requires Israel to prepare for such a scenario down the line. It is reasonable to assume, with a high degree of likelihood, that the IDF and the security establishment have already been preparing—organizationally and conceptually—for the potential realization of such a scenario, whether as a result of a deliberate decision that may be taken later or as a consequence of necessity. It should be emphasized that if a military government is eventually imposed, it must also include a civilian administrative component, tasked with handling the daily affairs of the Palestinian population and providing essential public services.

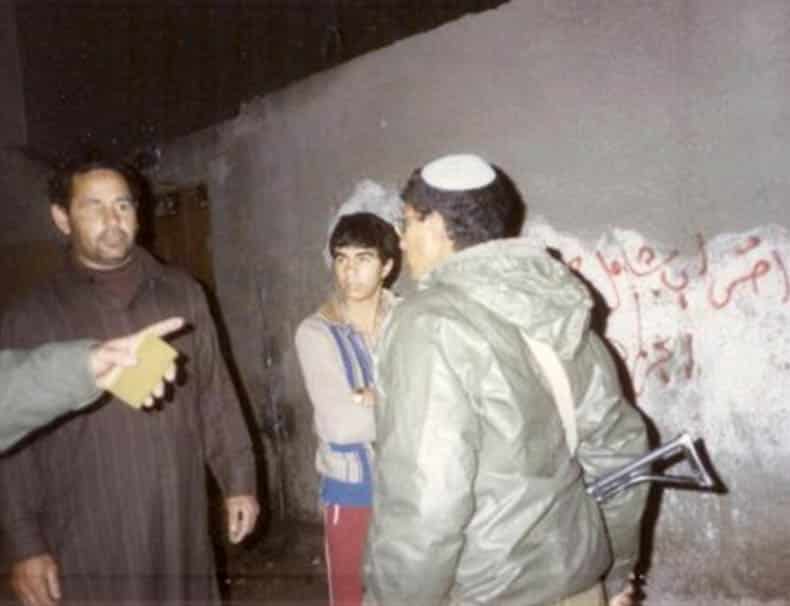

Based on my accumulated experience—having served for about eight years in the Gaza Strip as head of the Arab Department, which effectively functioned as the intelligence and special missions arm of the Civil Administration, including throughout the entire First Intifada (which began on December 9, 1987, and ended with the signing of the “Declaration of Principles” launching the Oslo process on September 13, 1993)—I will examine below the main relevant aspects associated with the issue of imposing a military government in the area. It is worth noting at the outset that, according to recent remarks attributed to “a source close to the prime minister,” Israel intends to promote the gradual conquest of new territories in the Gaza Strip, to increase pressure on Hamas to soften its positions in negotiations with Israel regarding a ceasefire and the return of the hostages.

The primary goal underlying the imposition of a military government in the Strip is to establish on the ground a strong and authoritative governing body that will deny Hamas the ability to recover, and thereby encourage the local population to cooperate with it and participate in the operation of public services and the management of daily life.

The re-establishment of an Israeli military government would, in practice, turn the wheels of history backward. Israel maintained such a government in the Strip during two separate periods. The first was following the conquest of the Sinai Peninsula during the Sinai Campaign in 1956, which lasted until the withdrawal of IDF forces in March 1957. The second was imposed about a decade later, after the conquest of the Gaza Strip in the Six-Day War of June 1967.

Since Israel’s conquest of the Strip in that war, the organizational and functional characteristics of the military government there underwent several changes over time. Following the war, a Civil Administration was established under the military government, comprised of five departments: Finance, Interior, Justice and Religion, Agriculture, and Services. The military government itself encompassed three districts: Gaza, Khan Younis, and El-Arish in northern Sinai. Israel assumed that civilian life under its administration would be short-lived, after which it would be transferred to local authorities. In practice, that assumption never materialized.

In September 1981, a separation was instituted between the military government and the Civil Administration, which was placed under the authority of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT). The Civil Administration was charged with providing public services and handling the daily humanitarian needs of the local population. It operated under COGAT, which in turn reported directly to the Minister of Defense. It supervised and directed the regional branches of Israeli government ministries (such as Health, Education, Welfare, Religions, etc.) that operated in the Gaza Strip. Each branch was headed by a staff officer (KAMAT) representing the respective parent ministry in Israel. The responsibility for guiding and overseeing actual activity was vested in the head of the Civil Administration, while the ministries themselves functioned on the ground through local Palestinian general directors. The responsibility for day-to-day management remained in the hands of Israeli military personnel and the staff officers. In the 1980s, nearly 5,000 local Palestinians worked for the Civil Administration in Gaza.

Until the outbreak of the First Intifada in December 1987, the Strip was administered by a military government roughly equivalent to a regional brigade. It functioned in three geographic districts: northern Gaza centered on Gaza City, central Gaza centered on Khan Younis, and southern Gaza centered on Rafah. During Israel’s rule in the Strip, significant financial resources were invested in these areas, particularly in developing the Palestinian healthcare system. Hospitals were upgraded with investments amounting to millions of shekels, modern departments were established, and institutions for training medical personnel were set up under the guidance of Israeli teams. The flagship project in this field was Gaza City’s “Al-Shifa” hospital, renovated in the 1980s by Israel with American assistance.

Following the outbreak of the First Intifada in December 1987, and to address the growing demands of day-to-day security, the IDF decided to expand its presence in the area and upgrade it from the level of a regional brigade (HATMAR) to a regional division (OGMAR). This division operated in the field through three separate brigades, each in a defined geographic area: the Northern Brigade, headquartered in central Gaza City in the building that had once housed the Palestinian Legislative Council under Egyptian rule; this brigade was responsible for ongoing security in Gaza City, for defending the settlements in northern Gaza, and for the Erez crossing. The second was the Central Brigade, headquartered in Khan Younis. The third was the Southern Brigade, headquartered in Rafah.

In addition, in 1989, the “Shimshon” Unit was established under the Gaza Division. This was an elite infantry unit whose soldiers would often disguise themselves as local Palestinians, allowing them to blend into the population and arrest inciters and activists involved in organizing violent disturbances against IDF forces.

A Different Reality Requires a Different Approach

Following the signing of the “Cairo Agreement” in May 1994, as part of the Oslo process, the IDF and the Civil Administration withdrew from the Strip. IDF forces then focused on defending the remaining settlements in Gaza and securing the border area. At the same time, the “Shimshon” Unit, which had operated in the Strip until then, was disbanded, with some of its soldiers joining the parallel “Duvdevan” Unit operating in Judea and Samaria.

Under the terms of the Cairo Agreement, the Civil Administration in Gaza was dismantled and its authorities and areas of responsibility were transferred to the Palestinian Authority. In its place, under the framework of COGAT, the “Coordination and Liaison Directorate” (CLA Gaza) was established, tasked with managing arrangements for movement, crossings, and employment in Israel for residents of the Strip.

Following the implementation of the Disengagement Plan in late 2005, on September 12, 2005, Southern Command chief Maj. Gen. Dan Harel issued a special proclamation announcing the abolition of the Israeli military government in Gaza. Two years later, the Palestinian Authority’s rule in the area also came to an end, when Hamas violently took control of the Strip, expelling PA and Fatah officials—many of whom were thrown to their deaths from tall buildings in Gaza City. During the “Swords of Iron” war, Brig. Gen. Elad Goren was appointed to oversee the humanitarian-civilian effort in the Gaza Strip, a role described by the media as a kind of governor of the territory.

For most of Israel’s years of rule in Gaza, a single regional brigade alongside the Civil Administration was sufficient to maintain effective control on the ground. Under current circumstances, however, such a force structure is insufficient and unrealistic. Beyond that, another significant difference lies in the size of the population, which directly impacts the scope of military presence required. In 1967, about 370,000 Palestinians lived in the Gaza Strip, and by 1987, that number had risen to some 570,000. Since then, the population has increased dramatically, and today approximately 2.2 million people reside in Gaza. If in the past a single brigade was enough to provide Israel with effective military-security governance, today the population is nearly four times what it was at the start of the First Intifada.

As expected, following the publication of the Security Cabinet’s decision, Hamas was quick to declare that Prime Minister Netanyahu’s plan to conquer the Strip proved his intention to sacrifice the hostages for his interests. “We emphasize that the Gaza Strip will remain unconquerable, and any attempt to expand aggression against the Palestinian people will exact a heavy and painful price from the occupation,” the statement read. Hamas added that Netanyahu’s remarks undermined the negotiations to end the war and “exposed the true motives” behind Israel’s withdrawal from the latest round of talks, which had characterized a narrowing of the gap between the sides. Hamas also called on Arab states, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and the international community to condemn Netanyahu’s statements regarding his intention to take over the Strip, to act to halt the war, and to bring the prime minister to trial before the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Military Government – Potentially “the Decisive Move”

The imposition of a military government in the Strip naturally entails high financial costs. These are required to fund the execution of ongoing security missions mandated by a permanent military presence on the ground. This is especially true in one of the most densely populated areas in the world, where IDF forces would be required to invest significant effort in consistently confronting terror cells that would continue to operate in the Strip.

As a side note, and with appropriate caution, I would point out that in my view, the figures circulating regarding the financial outlay required to fund the activities of a military government—estimated at around five billion shekels annually—are quite exaggerated, as are the force levels said to be needed, which are estimated at four divisions.

In conclusion, the establishment of a military government in Gaza would, in practice, constitute the decisive move that brings the “Swords of Iron” war to its end. The operational significance derived from this is clear: it would mark the conclusion of Hamas’s rule in the Gaza Strip, which began with its violent takeover of the territory eighteen years ago, in June 2007. However, it is important to note as a word of caution: the imposition of a military government will not allow Israel to rest on its laurels in terms of security. It will require the IDF, with close support from the Shin Bet, to continue a consistent and systematic struggle against terrorist elements in the area, with maximum attention devoted to ongoing security, prevention, and disruption of terror infrastructure and attacks against IDF forces.

And after all this, the imposition of a military government in the Strip is not, at present, on the agenda of Israel’s decision-makers, based on a recent statement by Prime Minister Netanyahu. Nonetheless, Israel must be prepared—both in terms of strategic planning and organizational-operational readiness—for the possible need to impose a military government at short notice. This is to avoid being caught off guard by unexpected developments and to ensure it can provide an immediate and effective response to such scenarios.

The decision to launch a broad and intense military campaign against Hamas in the Gaza Strip may ultimately lead the organization to agree to the renewal of indirect dialogue with Israel, to reach a new agreement on a ceasefire, and the release of the hostages. For Hamas, the feasibility of such a move would undoubtedly be motivated by the desire to prevent a devastating—possibly even terminal—blow to its military-political power in the Gaza Strip.