On March 22, 2025, 21 years will have passed since the targeted assassination of Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the man behind the founding of Hamas and one of the most prominent, meaningful, and intriguing figures in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yassin also played a central role in the development of the radical-militant Islamic movement inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood and in shaping the power dynamics in the Palestinian arena in recent generations.

Yassin was assassinated in the early morning hours as he was wheeled out of the mosque after morning prayers. Three Hellfire missiles fired from an Israeli Air Force helicopter ended his life. The attack also killed two of his bodyguards and six other Palestinians. More than a dozen Palestinians were injured in the operation, including two of Yassin’s sons.

Yassin was the driving force behind the establishment of Hamas in the Gaza Strip shortly after the outbreak of the First Intifada. Before that, he led the “Al-Mujamma’ al-Islami” association, which preceded Hamas. I knew him personally for over a dozen years, from the mid-1980s until his release from an Israeli prison in October 1997, in the course of my various roles in the IDF and the security establishment, notably as head of the Arab Affairs Department in the Israeli administration of the Gaza Strip. This department functioned as the region’s central intelligence body of the Civil Administration.

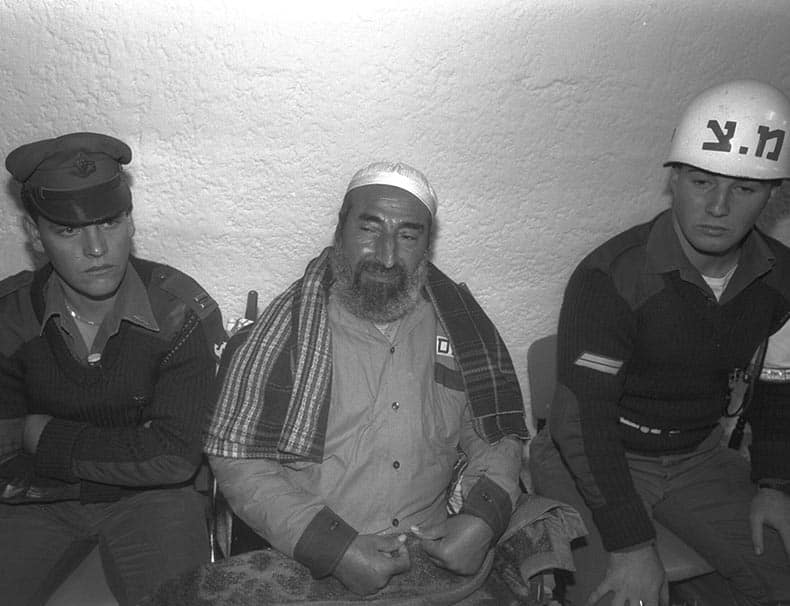

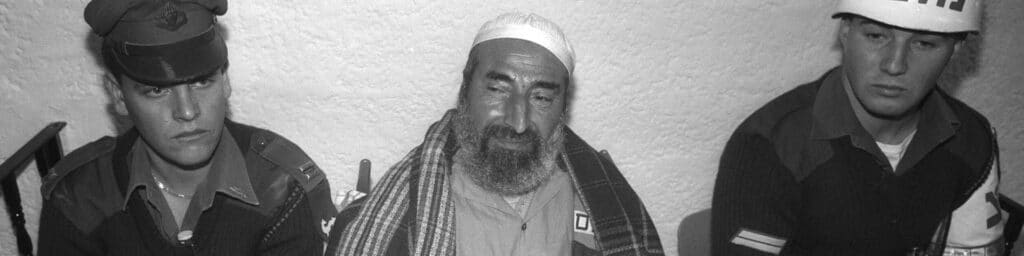

I met Yassin dozens of times in my office, which was located in the governmental complex of the Civil Administration in Gaza City, near the headquarters of the military government. We also met at his home in the Sabra neighborhood of Gaza City after his arrest in May 1989 and his trial before a military court, as well as in the Ashmoret prison where he was incarcerated and in the prison hospital in Ramla, where he was transferred for medical treatment due to the deterioration of his health while in detention.

Unlike other senior Hamas leaders, who displayed overt hatred and hostility in our meetings—something that was easy to discern from their expressions—Sheikh Yassin did not treat me in the same way. He was always matter-of-fact, answered my questions without evasion or reticence, and sometimes, I even thought he was pleased to see us. I must emphasize that I was fully aware of who he was and what he represented in all my meetings with him. His attitude towards me stemmed from the fact that he did not see me as a threatening or intimidating figure.

Sharp and Clear Thinking

Sheikh Yassin was born in the village of Al-Jura near Ashkelon on June 28, 1929. Following the War of Independence, his family was forced to move to the Gaza Strip and settled in the Shati refugee camp on the western coast of Gaza City. Over the years, different accounts emerged regarding the circumstances of his physical paralysis.

According to what he told me in one of our meetings, he was injured in his youth in 1952 while engaging in sports activities on Gaza’s beach. He claimed that he suffered a cervical spinal injury after falling while attempting a headstand. The young Yassin pushed his physical limits beyond what his frail body could handle, resulting in partial paralysis of his limbs, which worsened over time. In 1974, as he recounted, he could still stand when he performed the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj)—one of the five pillars of Islam. From the mid-1980s, however, his physical condition deteriorated further, eventually confining him to a wheelchair and requiring constant assistance.

Among his supporters as well as his rivals, a different version of his paralysis was widespread, claiming that it was the result of the torture he endured in an Egyptian prison in the 1950s. He had been arrested due to his activities in the Muslim Brotherhood, which the Egyptian government vehemently persecuted under President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Despite his severe physical disability, which greatly hindered his ability to speak and write, Yassin’s mind remained sharp and clear. He was focused and concise in his communication, frequently interweaving his words with quotations from Islamic tradition—the Quran and Hadith. Over time, he gained a reputation as a religious scholar and expert in Islamic traditions in Gaza and the West Bank and across the Arab world.

Although he never completed formal theological studies nor authored significant religious texts, Yassin was recognized as an essential and respected religious authority. I was struck by the fact that certain circles in the refugee camps attributed to him an almost saintly status, and his followers regarded him as a religious figure of the highest order, obeying his instructions immediately and unquestioningly.

In retrospect, Sheikh Yassin was undoubtedly the most senior, significant, and influential figure among the hundreds of Palestinians who Israel has targeted in recent decades.

The Israeli Recognition – The Original Sin

Yassin was the central figure behind the establishment of Hamas—“The Islamic Resistance Movement” (in Arabic: Harakat al-Muqawamah al-Islamiyyah). The organization was founded during a nighttime meeting at Sheikh Yassin’s home in the Sabra neighborhood of Gaza City on December 10, 1987, a day after the outbreak of the First Intifada. However, Hamas was not created as a completely new entity out of thin air. The organization was built upon an Islamic religious association operating in Gaza since 1973. It is called “Al-Mujamma’ al-Islami.” This association functioned as an ideological and organizational extension of the Muslim Brotherhood, which had been established in Egypt nearly 60 years earlier, in 1928, by Imam Hassan al-Banna.

Following Yassin’s request to the military government in Gaza—before the establishment of the Civil Administration as a parallel military-civilian body—the Israeli security apparatus officially recognized Al-Mujamma’ al-Islami in 1979 as an Ottoman association under the law governing non-profit organizations. Notably, the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs opposed this registration, warning the military government against granting legal recognition to the association due to concerns that it would engage in subversive activities under the guise of religious work. This recognition effectively granted the organization legal status, allowing it to operate freely and advance its ideological-religious goals.

From my perspective, the Israeli security establishment’s decision in 1979 to grant Sheikh Yassin’s request to recognize his association as a legal entity was Israel’s “original sin.” This decision reflected a superficial, short-sighted understanding of the potential dangers posed by an extremist Islamic association. The Israeli authorities failed to fully assess the risk that such an organization could radicalize the local population and eventually evolve into a hostile force aligned with other Palestinian factions opposing Israel. Beyond its involvement in protests and widespread unrest, the association had the potential to engage in direct terrorist activities within Palestinian territories and inside Israel.

Release and Return to Action

On June 15, 1984, Yassin was arrested and tried in a military court on charges of possessing weapons and explosives in his home and for establishing an underground organization aimed at fighting non-religious Palestinian factions and waging jihad against Israel to replace it with an Islamic state. In his defense, Yassin claimed that he had acquired the weapons only to defend himself against Fatah and leftist Palestinian factions, not for attacks against Israel. However, in one of our conversations, he admitted using this argument to influence the military court and seek leniency in sentencing.

His argument was rejected, and he was sentenced to 13 years in prison. However, less than a year later, in May 1985, Yassin was released as part of the “Jibril Deal”—a prisoner exchange between Israel and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, led at the time by Ahmed Jibril. Following his premature release, Yassin resumed his activities within Al-Mujamma’ al-Islami, picking up where he had left off before his arrest.

In 1986, under the umbrella of Al-Mujamma’ al-Islami, Yassin established “Majd” (an acronym for “Mujama’at Jihad wa Da’wa”—Groups for Jihad and Preaching) as an operational arm to combat those suspected of collaborating with Israel. This faction, which later became Hamas’s military wing, aimed to enforce Islamic law among the population and to target Palestinians accused of collaboration with Israel, as well as those deemed morally corrupt—thieves, drug dealers, pimps, alcohol sellers, and distributors of pornographic materials.

One of the key figures leading Majd was Yassin’s close associate, Yahya Sinwar. After his release from Israeli prison in 2011 as part of the Gilad Shalit prisoner exchange, Sinwar was elected head of Hamas’s political bureau in Gaza. Israel later assassinated him on October 16, 2024. I distinctly remember my only meeting with him, about a year before the outbreak of the First Intifada. I had summoned Sheikh Yassin for a routine meeting, and he arrived at my office accompanied by a young, slender man. “This is Yahya,” Yassin said—and said no more.

On October 18, 1988, about eight months after Hamas was officially founded, the organization, under Yassin’s guidance, published its ideological charter under the title: “The Charter of the Islamic Resistance Movement – Palestine, Hamas.” This document, which came into my possession shortly after its publication, was a distilled manifesto of the movement’s principles, worldview, and goals. The key tenets of the charter, which Yassin personally admitted to me that he had played a decisive role in drafting, included the imperative to liberate all of Palestine through holy war (jihad) against the Jews, the absolute rejection of any peace initiatives that involved territorial concessions, and the belief that jihad was the only viable method to restore the “occupied lands” to Islamic control.

“From the River to the Sea”

Let’s return a few months after the outbreak of the First Intifada in December 1987. The phone rang, and on the line was the poet Haim Gouri, who was working as a journalist for the newspaper Davar. The call from Gouri surprised me and was profoundly moving. He wanted to meet in Gaza to interview me and get a firsthand impression of the situation. My attempts to dissuade him from carrying out this journalistic mission in an area rife at the time with riots and acts of violence against soldiers and civilians were unsuccessful.

For the meetings with Gouri in my office, I invited Sheikh Yassin and two of the most prominent figures representing the spectrum of opinions prevailing in Gaza at the time—Dr. Haidar Abdel Shafi, head of the Red Crescent Society, was considered the undisputed leader of the left-wing camp, while Fayez Abu Rahma, chairman of the Bar Association, was regarded as the head of the Fatah camp.

I vividly remember Gouri’s meeting with Yassin. It was a surreal moment—the meeting of a poet from Israel’s founding generation, a former Palmach fighter, with a man who, just months earlier, had established Hamas with the explicit goal of destroying Israel. The meeting lasted for two hours, with me as the translator between Hebrew and Arabic, intervening only to clarify Islamic-Arabic terms that Yassin used.

Yassin answered Gouri’s questions at length, without hesitation or reservation. One of the questions pertained to how he viewed Israel’s existence as a Jewish state in the Middle East. “Look,” the sheik replied, “throughout history, there have been kingdoms and empires,” concluding with a rhetorical question: “And where are they today?” He continued, “There was the Roman Empire—where is it today? The Ottoman Empire—where is it today? The Third Reich in Germany, the British Empire—where are they today?” After listing all the collapsed kingdoms and empires, he concluded his remarks with: “Thus is Israel’s fate.”

Gouri was stunned, visibly shaken by Yassin’s words. Noticing this, Yassin attempted to reassure the Israeli poet, saying, “Don’t worry, we Muslims will be willing to recognize you Jews as Ahl al-Dhimma (protected people) under the wings of Islamic rule.” When the meeting ended, I told Gouri that Yassin’s statements reflected the broader Islamic doctrine espoused by radical Islamic activists—at its core, the aim to destroy Israel as a Jewish state and establish an Islamic state within defined borders, “from the river to the sea,” on its ruins.

The Return of the True Leader

The first wave of arrests among Hamas’s leadership took place in September 1988, delivering a severe blow to the movement. At the time, Israel refrained from arresting Yassin out of concern that such a step would immediately intensify the Intifada and escalate attacks against Israeli military and civilian targets. Sheikh Yassin swiftly reorganized the movement’s leadership, fearing that he, too, would soon be arrested. Indeed, following the murders of IDF soldiers Avi Sasportas and Ilan Saadon in early 1989, Yassin was arrested along with hundreds of senior Hamas operatives. He was tried in a military court and, on October 16, 1991, was sentenced to life imprisonment plus 15 years for leading Hamas, orchestrating assassinations of Palestinians suspected of collaborating with Israel, and establishing the organization, setting its goals, defining its operational methods, and raising funds to finance its activities.

The mass arrests of Hamas operatives in May 1989 effectively ended the movement’s initial phase of activity, concluding Yassin’s period as its supreme and exclusive authority and marking the end of Hamas’s leadership being based solely within the territories.

During his imprisonment in Israel, Sheikh Yassin was not entirely disconnected from the field. He remained informed about significant developments in the Palestinian arena and the state of relations with Israel. During this time, his status grew more substantial, and support for him increased, particularly among Hamas’s grassroots activists. However, following the kidnapping and murder of Border Police officer Nissim Toledano in December 1992 and IDF soldier Nachshon Wachsman in October 1994, I was requested by the Chief of Staff’s office to visit Yassin in his cell at Ashmoret Prison. The purpose of these meetings was to extract information from Yassin regarding the kidnappings and to relay messages through him to the Hamas kidnappers, urging them not to harm the Israeli hostages and to facilitate negotiations with the Israeli authorities for their eventual release.

Yassin immediately agreed to my requests, and in two meetings held with journalists in the prison’s conference room, he publicly called for the hostages to be spared and for negotiations with the Israeli authorities. Unfortunately, his appeals to the kidnappers in both cases were brushed aside.

On October 1, 1997, just eight years into his imprisonment, Yassin was released from Israeli prison. His early release was part of a deal brokered between Israel and Jordan following the botched Mossad assassination attempt on Hamas political bureau chief Khaled Mashal in Amman on September 22, 1997. After this incident, Yassin was transferred from the medical wing of Ramla Prison and flown by Jordanian helicopter to Amman in response to a request from King Hussein of Jordan. He arrived in Gaza on October 6, 1997, where the Palestinian Authority officially welcomed him. The following day, Yasser Arafat visited him at his home.

Following his release from prison, Yassin resumed his position as Hamas’s leader. As a result, the movement’s center of gravity shifted to the Gaza Strip, and public support for Hamas surged. The sheik did not change his stance; in his public statements, he conditioned any ceasefire with Israel on terms that Israel could never accept. Moreover, he renewed his operational activities against Israel—not only through preaching and incitement but also by approving and directing terrorist attacks against Israeli civilian and military targets.

Yassin’s early release gave Hamas a significant moral boost. He rode the wave of public admiration, reestablishing himself as the movement’s leading figure in the Palestinian territories and among Hamas supporters in exile.

The Assassination, Recovery, and Takeover

The targeted killing of Sheikh Yassin took place on March 22, 2004, but his position did not remain vacant for long. Immediately following the operation, Dr. Abdel Aziz al-Rantisi was chosen to replace him. Rantisi was one of the prominent activists surrounding Yassin within the Al-Mujamma Al-Islami association. He had also participated in the meeting held at Yassin’s home a day after the outbreak of the First Intifada, during which the decision to establish Hamas was made.

It is important to note that Rantisi did not have much time to leave his mark in his new role, as only a few weeks after being appointed as the leader of Hamas, on April 17, 2004, Israel also carried out a targeted assassination against him.

The elimination of Yassin was undoubtedly a strategically significant move for Israel. It dealt Hamas a severe—though not fatal—blow, both operationally and morally. While it removed the founding father, who was regarded by rank-and-file members of the organization, as well as many in the Palestinian and Arab spheres, as a leader of great stature and a heroic symbol, the shock that struck Hamas after the assassination did not last long. The organization managed to recover within a relatively short period.

This recovery was facilitated, among other things, by actions taken by Israel, most notably the implementation of the Gaza Disengagement Plan, which was completed in November 2005. The Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip provided Hamas with a significant boost, and its victory in the Palestinian Legislative Council elections in January 2006—held in Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem—enabled it to establish the Palestinian National Unity Government, led by senior Hamas official Ismail Haniyeh.

Hamas’s growing influence in the Palestinian political arena did not stop after the parliamentary elections. Another critical turning point came in June 2007, when Hamas militants seized control of the Gaza Strip by force, expelling the Palestinian Authority from power. This takeover was marked by violent measures, including throwing dozens of Fatah and Palestinian Authority activists from the rooftops of high-rise buildings in Gaza City to their deaths.

In Palestinian historiography, this event became known as “the coup against legitimacy.” Following Hamas’s takeover of the Gaza Strip, the geographic and political division that still characterizes the Palestinian arena was cemented. In practice, the Palestinian political landscape split into two separate entities: the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.