At the end of 12 intense days of fighting in Operation “Rising Lion”, Israel achieved a historic and overwhelming victory over Iran’s ayatollah regime, and it is already clear that this achievement has triggered significant tectonic shifts in the Middle East’s balance of power.

Before the war, Iran and the “Axis of Resistance” it controls—in Gaza, Lebanon, and Yemen—were perceived primarily as a force with significant deterrent capability. This perception prevailed not only in Israel but throughout the Middle East and beyond. However, this picture changed dramatically thanks to the awe-inspiring performance of the Israeli Air Force and intelligence services. As the dust of war began to settle, it became clear to all players around the Middle Eastern chessboard that Tehran had indeed lost its deterrent status. Now, considering the new balance of power that has emerged after the war, it can be said that the vacuum created by the severe blow to Iran has been filled by two rising regional powers: Israel and Turkey.

As a country bordering Iran and, in a sense, Israel—via Syria and the eastern Mediterranean—Turkey followed developments in the war with great interest. From Ankara’s perspective, although it ostensibly adopted a pro-Iranian policy from the outset of the war, in practice, Iran’s significant military humiliation and the loss of its military capabilities were a welcome development for the Turks.

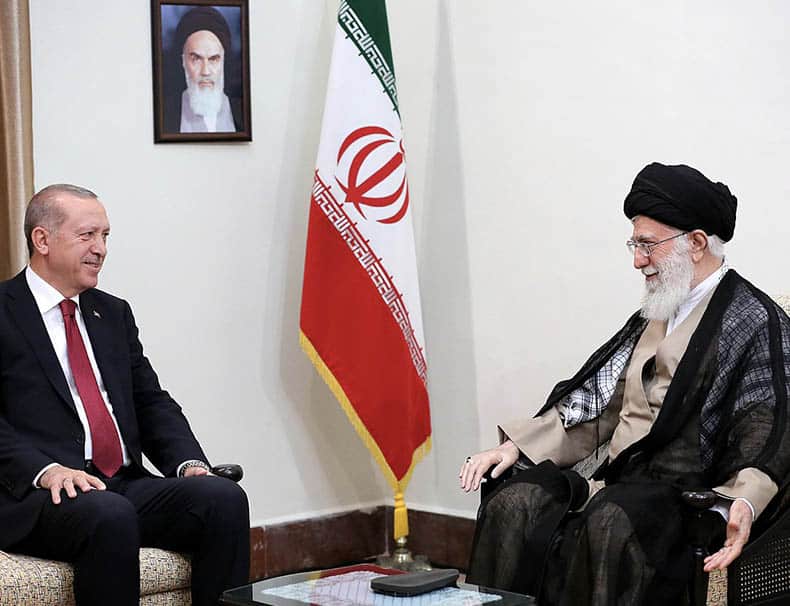

With Iran’s decline, Turkey began to “play” more openly in the competition for leadership of the Islamic world. It is no coincidence that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared in his speech at the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) summit in Istanbul on June 21 that “Istanbul’s fate cannot be separated from the fate of Tehran, nor the fate of Gaza, Sana’a, Damascus, Cairo, Jerusalem, Mecca, and Medina.” In the same breath, Erdoğan called for transforming the OIC into a more active, unipolar deterrent force.

Against the backdrop of the Turkish president’s speech, it can be concluded that compared to the pre-war period, Ankara now finds itself in a stronger political position. Nevertheless, thanks to the war, Ankara has also become aware of its weaknesses and therefore now seeks to improve its strategic capabilities by learning lessons from the conflict.

At this stage, Turkey will focus on three main issues from its perspective. The first is correcting intelligence weaknesses. The fact that Israel managed to neutralize more than thirty senior Iranian officials in the regime’s decision-making apparatus right in the opening strike of the war is seen in Ankara as an essential lesson to learn. As reflected in the Turkish media, it has been decided that, in light of the war’s lessons, the security circle around decision-makers will be strengthened. At the same time, crucial passive defense measures such as building shelters and bunkers will also be undertaken.

In addition, the first Israel-Iran war exposed the immense importance of air defense systems. Turkey has already been working on developing systems similar to Israel’s Iron Dome, David’s Sling, and Arrow, under the name “Steel Dome.” It is clear that after the war, additional efforts and resources will be invested in these developments.

While the first two issues focused mainly on Tehran’s weaknesses, Turkey’s third conclusion concerns ballistic missiles, which Turkish decision-makers have given priority in light of the destruction Iran caused to Israel’s home front.

Unlike Iran, despite the presence of a strong navy and air force, Ankara had already decided to develop ballistic missiles before the war. Although serial production has yet to begin, it is clear that additional time and resources will now be allocated to existing ballistic missiles—the “Tayfun,” with a range of 560 km, and the planned “Cenk,” with a projected range of 3,000 km, which are still under development. There is no doubt that these decisions will further enhance Turkey’s deterrent power compared to what it is today.

Between a “Security Threat” and a “Potential Enemy State”

Although Turkey is pleased to see Iran’s military weakening, it also fears a complete collapse of the regime. This fear is not ideological; the main reason is concern that if the regime falls, Iran could disintegrate into separate ethnic groups. In such a case, Ankara fears that the Kurds living in Iran would attempt to reestablish the historic Kurdish Republic of Mahabad, which functioned as the first and last independent Kurdish state in modern history. Undoubtedly, such a development could trigger a wave of separatist-nationalist sentiment among the Kurdish population in Turkey.

However, it would not be accurate to say that all developments in such a scenario would be detrimental to Turkey. It is well known that millions of citizens of Azerbaijani origin—who are considered an integral part of the Turkic family of peoples—live in northwestern Iran. In the event of regime collapse, it can be assumed that this ethnic group would seek to unite with the independent Republic of Azerbaijan to the north, which is a sister state of Turkey. It is important to emphasize that despite the potential benefits for Turkey in such a scenario, it still has no interest in Iran’s disintegration. From this, one can deduce a significant gap in understanding foreign policy between Ankara and Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.

Alongside Azerbaijan, Israel would be the biggest beneficiary of the instability that would result from the collapse of the Iranian regime. Since such a collapse would reduce the strategic pressure on Israel’s national security, Turkey would likely, once again, have no interest in the complete disappearance of the regime in Iran.

With the outbreak of the war initiated by Hamas against Israel on October 7, Turkey shifted its pro-Palestinian policy to a pro-Hamas stance and began taking a highly confrontational position toward Jerusalem. In October 2024, relations reached a new low when Turkey declared Israel a security threat in a historic closed-door session of the Turkish parliament. Later, in January this year, this declaration was explicitly mentioned in the “National Security Policy Document,” also known as the “Red Book,” which defines external threats to Turkey. As if that were not enough, similar statements were made by the Turkish Foreign Ministry and other senior Turkish officials.

In response, Israel addressed these developments. It conveyed its discomfort to the Turkish side regarding Ankara’s new status in Syria after the fall of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. The leak of the “Nagel Report,” which advised the Israeli government to change its security perception of Turkey and define it as a “potential enemy state,” played a very significant role in delivering these messages to Ankara.

Turkey “Smuggling” Syria into the Abraham Accords

In light of all that has been said, and considering that Turkey and Israel were left alone at the top of the Middle East after Operation “Rising Lion”, it can be said that the rivalry between the two countries will deepen further. However, despite this tension, it is also important to emphasize that the two countries have maintained full diplomatic relations since 1949, which prevents Jerusalem and Ankara from taking active, hostile steps against each other.

While this “cold war” continues between Jerusalem and Ankara, it has recently been reported in the media that a new wave of Abraham Accords is blowing through the Middle East. In other words, Jerusalem is on the verge of completing its military victory over Iran and the “Axis of Resistance” it created, by achieving peace with moderate Arab states. At this point, reports have emerged suggesting that even Syria might join the peace convoy.

This spirit of peace is not welcomed in Ankara. Ironically, although Turkey was the first Muslim country to recognize the State of Israel in 1949, it does not support peace between Israel and other Arab countries. In other words, Ankara prefers Israel to remain isolated. Proof of this is the Abraham Accords of 2020; similar to today, back then, Turkey was also opposed to the initiative, sharply criticizing the United Arab Emirates and accusing it of betraying the Palestinian cause.

Even today, it can be assumed that Turkey will adopt a similar stance, especially regarding Syria, which, according to recent reports, is intended to be brought into the Abraham Accords in one way or another. Even after Assad’s fall, the Turkish military occupation in northern Syria continued, and through various logistics and infrastructure projects, Ankara has created a serious dependency on it in Damascus. In other words, Turkey will not be willing to lose its influence if Syria were to join the Abraham Accords bloc.

From the Syrian perspective, it seems that this dependency has reached such a high level that we see Syria, under the leadership of Ahmad al-Sharaa, approaching Israel and the U.S. in order not to lose its independence to Turkish hands. Thus, Damascus is deliberately drifting toward the “Abraham Accords bloc,” which includes Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan, and is externally supported by Egypt and Jordan. All these steps have been built gradually on a foundation of “realism,” as if they were written in an introductory textbook on political science theories.

In conclusion, Operation “Rising Lion”, was not just a military confrontation between Israel and Iran, but a historic turning point that led to seismic shifts in the Middle East’s power map. Thanks to its sophisticated intelligence network and air power, Israel dealt heavy blows to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic capabilities. Thus, with its “long arm,” the small Middle Eastern state significantly increased its regional deterrence capacity. Conversely, Iran’s failure to defend itself and mount a large-scale offensive weakened its regional standing.

This dramatic development created a new regional vacuum, turning Israel and Turkey into central players filling the gap that emerged. Turkey, which closely followed the war, drew strategic lessons, particularly in intelligence, air defense, and ballistic missile development, and thus began a process of rebuilding its military capabilities.

However, the post-war picture is not limited to technical or military dimensions alone. The consequences of the war revealed the deepening rivalry between Turkey and Israel. As the two countries become increasingly isolated at the pinnacle of the Middle East, they have turned into two poles that avoid direct confrontation while also trying to encircle each other’s influence. While Israel seeks to complete its military victory with new peace initiatives in the Arab world, Turkey approaches this normalization process with skepticism and even suspicion.

The possibility of Syria joining the Abraham Accords stands in stark contrast to Ankara’s regional priorities. As a result, the new equation created after “Rising Lion” opens the door to a new era in the Middle East, deepening both the polarization and the struggle for regional leadership, which creates the cold war between Jerusalem and Ankara.